Repatriated from Beirut in 1946 / Currently resides in Yerevan

Repatriated from Beirut in 1946 / Currently resides in Yerevan

Dexcanik Grigoryan

I remember it well. The envoys came to Damascus and started to preach and convince people to come to Armenia. The Tashnags were very opposed to it and the Hnchags, naturally, supported it. The people were enthusiastic. It was bedlam. My father worked in favor of repatriation. One group of envoys would leave and another would arrive. They said that there was work in Armenia and homes were ready. The chickens, they said, were laying eggs under the walls and that people could go and collect them.

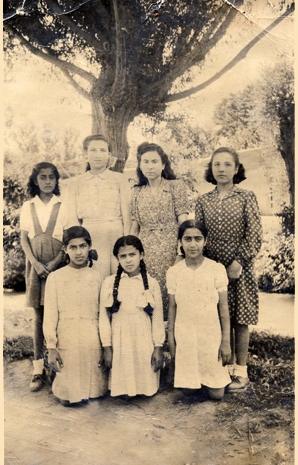

They sent groups of people from the port in Beirut. They put us up along the shore in cabins, Blankets were on the ground. We waited for days for the ship. Our relatives came to see us off. Joy on one side, and crying on the other. I was photographed with my grandfather for the last time in the quarantine zone. I have that photo. My father left his elderly parents there because his father was a Tashnag.

We arrived on the ship Pobeda. We came singing and dancing.

The road to Armenia is stony, stony,

Stalin misses us, misses us,

Hey jan, Yerevan, pretty Yerevan.

Thus we came singing. We were so naïve that we didn’t thinks that we were going to a country that just came out of a war.

We experienced great disappointment when we reached Batum. My father saw that the women were dragging some carts, transporting goods. He told my mom, “Vartuhie, we are done for.” All the people were disillusioned on the ship. They gave us bread. When squeezed, water dripped out. It was black bread. They told us it was kneaded with wine.

We were also in open quarantine in Batum. I think it was Ofelia Hambardzumian that came and gave a concert there. She was a young girl.

They took us to Armenia on transport wagons. There were ten families in each wagon. We entered Armenia in a dirty stench and noise. But when people saw the mountains of Masis they were overwhelmed with joy. We forgot all those hardships.

Those repatriates who arrived before us came to the station, to see if their relatives had come or not. The mother, aunt and other relatives of Levon Ter-Petrosyan had come to greet us. Upon seeing us, they were so glad they didn’t know what to do. “Vay, Vartuhie, you’ve come as well?”

They gave us fruit in the train, as well as bread, cheese and salami. It smelled terribly. My mother told Levon’s aunt, “Sima, I’m getting rid of this cheese. It smells.” She said, no, don’t discard it.

As luck would have it, so much snow fell that year that you couldn’t walk. Women were walking around in the cotton jackets of their husbands, returned from the war, and wearing slippers. There were still German prisoners of war in Armenia. They built the tramway line stretching from the outskirts of Yerevan.

They took the repatriates that arrived with us to Sisian, Goris, Dilijan, Kirovakan and even to remote villages. They left us in Yerevan. Later, the government gave us a plot of land and a loan to build a house. But, in those years of famine, who was building a house? People were building small huts and used the loans to buy food.

There were only Finnish barracks and a few stone huts. People moved inside until they built their houses. That’s how the Yerevan neighborhood of Zeytoun came about. It was a barren place where wolves roamed. This neighborhood was built in 1946. Victory Park and the Monument were built during our time. There was nothing; deserted. We were pupils and walked down to the Pioneer Palace. There was no transportation. There was nothing at all.

I don’t get involved in politics, but I know that our arrival was necessary so that the population would increase and Armenia wouldn’t turn into an autonomous republic. So it wouldn’t be attached to Azerbaijan or Georgia. But at least they should have explained it.

The locals greeted us with swords. Perhaps they thought that they had no work or food and here we are to take their share. When we arrived, they forgot about the exiles from Western Armenia in 1915 who they called refugees. They started to ridicule us, calling us akhpars. We didn’t give our girls to the locals to marry, nor did they give us their girls. There were locals who called us ‘dirty akhpars’, and there were repatriates who called the locals ‘dirty dogs’.

The KGB checked our letters. We used code words amongst us. Then the exile started. We’d wake up in the morning to find that our neighbor had vanished. They would come in the night, in closed cars and take them to Siberia. There were cries and wails. Those traitors were amongst us, but no one knew what information they were providing.

At the time, Siberia needed people. Many of those with relatives overseas were taken away. They gave nothing to the family members of those who were exiled.

We were also afraid of being banished because my father, in the beginning, acted very rudely since they had tricked us into moving here. But nothing of the kind happened.

After Stalin died people were exonerated and returned. There were many escape attempts from Armenia, especially with the young people. One of them, my brother-in-law, was caught trying to escape while living in Leninakan. He spent five years in prison.

They didn’t employ repatriates at the local party committees. They regarded us as suspicious. They even didn’t give us jobs as sweepers. Yes, I worked at the people’s education section, but that was in the 1970s. My father, by the way, was a communist party member and received a pension.

The repatriates brought trades to Armenia. They were good barbers, tailors and shoemakers. They were used to private business. They worked in plants and factories but plied their trades at home. When the financial inspector found out, he would come to collect his bribe to keep quiet. The government didn’t permit private business.

The repatriates also brought new foods with them. Locals had never seen an olive or coffee. They would say – these akhpars eat all kinds of junk. Once, my husband brought a banana. It was the first time the store got a supply.

We are two sisters. My sister gathered her family and left Armenia. I didn’t because I had a good job and was loved and respected. I didn’t focus on the small stuff. Then too, I love my country. This is our home and our family. Who will throw us out of here? In Syria or Lebanon, whenever you had a run-in with the Arabs, they’d say – go back to your own country.