Repatriated from Bucharest, 1946 / Lives in Yerevan

Repatriated from Bucharest, 1946 / Lives in Yerevan

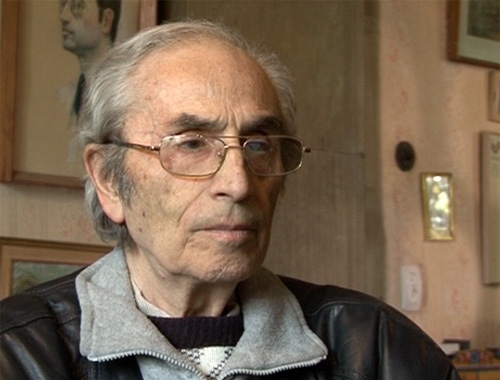

Sargis Jamkochyan

My father taught me Russian when I was a young boy in Rumania. He was from Ghars, lived in Tiflis, and then moved to Rostov, Batum. He resided in Constantinople from awhile before moving to Rumania.

Red Army officers would come to our house there. One day, one of these officers came and said, “Mr. Garegin, I am going to Armenia.” I was 12 or 13 at the time. I jumped up saying, dad, should I go and see him off? He said, go. The ship was anchored and the officer took me on board to show me around. My heart wanted to go to Armenia.

I said, “I am coming with you, grandpa Mkho.” That grandpa Mkho turned out to the head of the university’s military faculty. He told me, “No, boy, you will be coming with your father and mother. There will soon be a repatriation.” Simply put, it took a long time for that man to convince me. I left the ship and remained with my parents.

Months later, we too arrived in Armenia by ship. It was 1946. We reached Batum and they ordered us to throw all our food and sweets into the sea. The sea turned white. The birds were eating it all. We were watching it in awe. But we disembarked from the ship and they gave us black bread. They then loaded us in cargo wagons for the trip to Armenia.

We knew that we were coming to a country that had just exited the war and that there would be hardships. But we didn’t expect that level of hardships.

Now, I wonder why the authorities of the day didn’t sit down and think what they needed to do so that the people they were bringing wouldn’t experience a tragedy. We didn’t know how to continue with our lives. My father got work with great difficulty. He was a tailor.

And you know what? If you tell a person that you will give half of his house to some strange newcomer, and that he will live in difficulty, that person will never voluntarily accept such a thing. That’s what happened to us. When they took us to Sari Tagh in Yerevan and the people gave us their one room, I don’t know if it was an animal shed or not, they were very much opposed to it, in spirit, but they never openly said so. They could hardly all fit into that one room themselves.

In 1949, they exiled Mazmanyan who lived in the house next to ours. We learnt of it in the morning and were very scared. Mt mother began to put our clothes in a bag just in case they came to take us. Luckily, they never came, but Mazmanyan’s family disappeared. He was a shoemaker. He was a liberal thinker and spoke openly about life and its inadequacies.

I graduated from the Institute of Foreign Languages. I knew French as a child. Later, I saw that there was nothing I could do with my knowledge of French in Yerevan. There were teachers all over the place. So I went to the provinces and worked as a teacher for two years.

I then left for Moscow and another world opened before me. I knew two foreign languages. As the Russian saying goes, one hand stole from the other. There weren’t many Rumanian translators and it seemed that in one day they all learnt my telephone number. The House of Friendship, the House of sporting Events, the Concert Hall…They would telephone and say, “Mr. Jamkochyan, can you do such and such a job for us? I worked there for two or three years and then returned.

When I reached Yerevan, the Ministry of Enlightenment immediately called. “Mr. Sargis, we want to organize French evening classes for specialists.” I responded, fine. So I returned to Moscow and hauled the necessary books back for the classes.

The classes were held next to the Maksim Gorky School. I hired the teachers from my circle of acquaintances. They were professionals trained overseas.

Once a year, we were supposed to meet with the Catholicos (Vazken I). We would get specially prepared and buy gifts for the Catholicos. We would take group photos. The Catholicos remembered Vardouhie Varderesyan and he knew all our names. Naturally, we were happy inside that we had such a Catholicos who was also a Rumanian-Armenian who did so much for the church.

He arrived and on the first day he gathered a group of architects and told them that they were to restore all the old churches and temples. He didn’t want to struggle as a man of the church, but he became such a great authority in the eyes of the communist rulers that his reputation rose to great heights in an atheistic country where it was even impossible to talk about religion.

I was travelling to America back in the communist era because all our relatives from Rumania had moved to America. They sent me an invitation once. I went and returned within the time allotted. After that, I had no problems. I visited and returned some ten or twelve times, for two-three months. In those thirty years when I would go and return, I would always ask myself whether I should live in America or Armenia. In the end, I could never decide. I’ve lived in Armenia because my circle of friends is here, my language is here, and so are the graves of my relatives.

Regarding our way of life, it’s unbecoming to say so but we have remained repatriates until today. I talking about our family. My wife and I, and to a certain degree our children, haven’t changed in terms of our traditions, customs and morals, etc.