1946-49

Towards the Fatherland

Emerging victorious from World War II, the Soviet Union wanted to expand its zones of influence not only in Eastern Europe, but also in Turkey and Iran. In its project to have access to the Black Sea straits, there was also the issue of uniting the provinces of Kars/Ardahan to Armenia and Georgia.

To make its demand more convincing, it was decided to play the Armenian card. It was necessary to explain to the Allied Powers (Great Britain and the USA) that its territorial demand regarding Turkey wasn’t mere aggression but the restitution of Armenian rights lost as a consequence of WWI.

At the Potsdam Conference, the Allies naturally rejected this project of the Soviet Union. Soon afterwards, the USA dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, thus radically altering the global geo-political balance. In 1947, with the declaration of the Truman Doctrine, it became clear that Turkey enjoyed powerful backers and that the Kremlin must accept the inviolability of the Soviet-Turkey border.

At the same time, in the spring of 1945, when the war still hadn’t ended but the victory of the Soviet Union was already clear, preparations for the Great Repatriation to Armenia began. Authorities in Armenia, encouraged by the prospect of launching a new and more extensive immigration process, attempted to persuade Stalin and his entourage of its merits, in order that the repatriation of Armenians could begin as soon as possible.

Stalin, however, was in no hurry, because he realized that the country, having just gotten out of the war, was in no condition to accept a mass inflow of immigrants. Nevertheless, such a flow of people was needed to show that the Soviet Union was indeed an attractive destination for thousands who desired to relocate there. In this context, the Armenians weren’t a singular case. Russians, Ukrainians and other nationalities were also returning to the U.S.S.R.

The signal to launch the repatriation had been given. The prospect to unite certain historic Armenian lands to Soviet Armenia was being discussed in diasporan Armenian communities. Not to back such a pan-national project would greatly discredit the Soviet Union. It would also reinforce the anti-Soviet stance of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), the most influential structure in the diaspora, which was regarded as an opponent, if not enemy, by Soviet authorities ever since 1921.

After examining the issue from all sides, on November 21, 1945, on the eve of the 25th anniversary of the establishment of Soviet rule in Armenia Stalin signed a decree permitting Armenian repatriation.

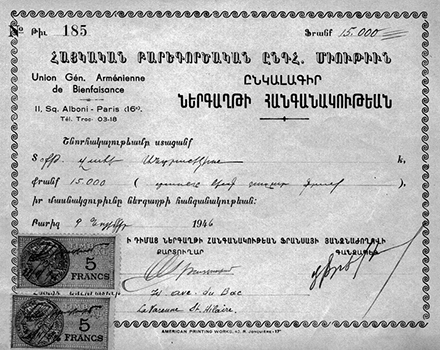

Registering those who wished to relocate to the homeland took off in diaspora Armenian communities. According to unverified data, 300,000-450,000 Armenians in over ten countries expressed a desire to relocate.

Instructions were given to primarily recruit the destitute and those able to work. But local immigration committees had no reason or stipulation of turning away those who applied. The only stipulation made was to members of the ARF – they had to leave the party in order to repatriate. Many ARF members decided to comply and published their resignations in pro-Soviet and progressive diasporan periodicals.

The first ship left Beirut in July 1946. After reaching Batumi, the repatriates traveled on to Armenia by train.

The reality when they arrived was quite different from what they had heard about Armenia and what they imagined the country to be. Instead of the new residences they had been promised, the repatriates were housed with locals or in structures never designed for occupancy. Instead of the cornucopia of plenty they had been promised, the new arrivals were shocked by the long bread lines and empty store shelves. Craftsmen who had lived in towns and cities prior to relocating wound up in rural communities where there was no business and thus no means to make a living. Those who had lived in valleys were sent to mountainous areas, and vice-versa.

Of course, this wasn’t done intentionally or to pursue some predetermined purpose. Rather, it was the result of poor planning and inadequate organization, and the issue was discussed and evaluated within governing bodies in Armenia and the Soviet Union.

Despite it all, the wave of repatriation continued. In 1946, Armenia accepted 50,918 individuals from six countries – Syria, Lebanon, Bulgaria, Iran, Romania and Greece. In 1947, 35,422 individuals repatriated from Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Greece, France, Egypt, Palestine and the U.S. In 1948, 3,092 individuals repatriated from Romania and Egypt. In 1949, Armenia accepted one convoy of 162 individuals from the U.S. on a special basis.

The gradual drop in numbers wasn’t due to a disillusionment of repatriates. Even if they wanted to, the new arrivals couldn’t advise their friends and relatives back home not to make the trip. It was very dangerous to express a negative/unpleasant opinion regarding Soviet reality.

While tens of thousands were waiting in the diaspora for the chance to relocate to Soviet Armenia, the repatriation project gradually waned and eventually shut down because the authorities of both the U.S.S.R. and Soviet Armenia saw the terrible contradiction between the task they had assumed and the actual prospects to achieve it.

In any case, what did Armenia get from the repatriation process?

A bit more than 90,000 Armenians relocated to Armenia in the span of four years. The work force was buoyed with villagers, laborers and craftspeople who injected a new culture of work and a new lifestyle. The young people and children who relocated would take advantage of free public and university education in Soviet Armenia, becoming professionals, scientists and cultural figures. In general, Armenia benefited from this mass-scale project. The repatriates benefited as well. But the Soviet regime, given its authoritarian nature, didn’t allow the Armenia-Homeland connection to be stable.