Immigrated from France in 1947

Immigrated from France in 1947

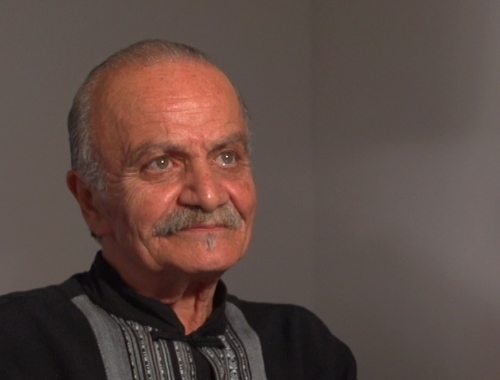

Alen Pirian

When we immigrated to Armenia, my father knew that the country had just gotten out of the war. So he put everything into two containers and took them to Armenia in order to build a house. And it was that house that caused us grief in the end. My father had a parcel of land behind the printers in Yerevan and wanted to build a three story house there.

I was young. They had place me in a Russian kindergarten, arguing that it was best if I learnt Russian. I would pick up Armenian anyway. I would get ahead if I knew Russian.

There was a hospital on Abovyan Street. We lived at the end of the semi-basement floor. I believe it was 1949, in June. They knocked on the door. All of us awoke to an amazing sight. There were soldiers and an officer; with guns un-holstered. They said that the situation on the border was quite bad and that we had to move there. They told us to take whatever we could handle.

So, they put us in a truck with other families. We started going down Amiryan. There were trucks all over, filled with people and families. They were headed towards the station. They placed us in cargo railway cars that had been made into two levels inside.

We stayed in the cars, in the dust and rain, for three or four days before the train got moving. The doors were open, but there were two soldiers standing watch. On each of the floors in the cars there were fifty or sixty people; kids and all. There was nothing to eat or water to drink. If the train stopped at a station, we got some water and those with money bought something to eat. They would hand it out to the others.

I was five years-old. I would play and didn’t feel a thing. But I can imagine how hard it was for my parents. We spent seventeen days on the road. We reached this place and were again placed in trucks. We traveled on and were then let out in this huge forest where there were four-five barracks. They put us inside. The barrack was a long building with a corridor and rooms running down it. Each family had a room. There was a Russian stove made of brick in the middle.

My father was forced to chop down trees. They chopped for nine months. In July, when the River Ob was free of ice, they ferried all those trees down river. It was very hard for the parents. Very hard, in my opinion. They couldn’t send the kids to school because there was none. They couldn’t keep us warm. They let us go outside and we were happy because we could play.

My father met up with a former POW who was also chopping trees. The guy asked, “Pirian, how did you wind up here? You related your life story. You sacrificed a child for France. France and the Soviets were fighting against the Germans. So how did you wind up here? I don’t understand. I fell prisoner and that’s why they sent me to Siberia. But you? If you permit me, I’ll write a letter on your behalf.” The officer wrote a letter.

Two years go by and we receive a letter saying that our case is being reviewed. Later, we went to another village. I just found it on the internet – Tyagun, Altay region. I would ski to school; seven kilometers there and seven back. The temperature was -52 centigrade. It was awful, but I survived. You had to pay attention to your hands and feet. If you covered your nose and ears, nothing would happen to the rest of you. Hey, we were kids playing. Our blood warmed and we didn’t feel it.

They then summoned my father to Novosibirsk. He went and was told that a great mistake had been made and that he shouldn’t have been brought there. It was 1952 and Stalin was still alive. We returned. When we got off the train at the Yerevan station, they immediately asked for our papers. They told us to follow them to their office at the station. I remember it as if it happened today. The officer, holding our papers, said, “Look at these four people. They are the most unsoiled people in the Soviet Union. We have checked everything from their toenails to the hair on their head.”

But we didn’t have a house in Yerevan. We later heard the story. A lieutenant-colonel with the internal affairs committee had his eye on our house. He made the arrangements to have us deported. They gave us some land on Djrashat Street. They also gave us a loan. So my father started building another house. I graduated from the Russian school and was accepted at the architecture faculty at the Polytechnic Institute. I worked during the day and attended class in the evening.

In 1965 we got our papers and came to France.

I haven’t encountered any problems here. When I got here I was 26. I didn’t know French, so I two classes for two months. I read, watched TV and went to the movies. But I had to start working. I looked for work with my cousin in Marseille. An architect worked at the first door we knocked on. He hired me. It was there that I began speaking French; I had to. He doubled my salary the following month and gave me a difficult project.

I have no diploma from Armenia since I left school. But they certified all my papers and work history at the French consulate. At the time, German, American or Belgian diplomas weren’t accepted in France. But the Armenian, the Yerevan Polytechnic Institute diploma, was accepted. Later, I presented my diploma work and received a French architectural diploma.

I visited Armenia in 1978, thirteen years later. Much had changed. Most importantly, I tracked down my friends.