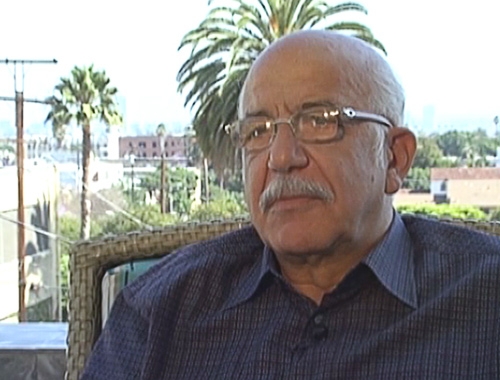

Repatriated from Beirut , 1947 / Lives in Los Angeles

Repatriated from Beirut , 1947 / Lives in Los Angeles

Hagop Moushoyan

I remember the jubilation our family and everyone experienced on the ship going to Armenia. It was a beautiful evening when we reached Batum; the sky was streaked with red rays. It was as if we had arrived in paradise. Sure, I was young, but I understood how my family’s joy slowly evaporated.

They moved us to a two room apartment in Leninakan. Six people were living there. They gave us on of the rooms, again for six people. They left the other room for those poor people. It was a difficult time for them and us. During those first days, my father and the landlord argued. It was only natural. The apartment belonged to them and all of a sudden they gave half to others.

My father realized we couldn’t stay there for long. After three months, we rented another place and moved out. But I appreciate that the other family was able to put up with us for three months in their home.

My father was constantly trying to keep our spirits high. He was a dedicated communist and a political prisoner in Lebanon. My joy was extinguished in 1949, when the deportations started. At the time, people would gather in our home, waiting to see what tomorrow would bring. Slowly, the fear subsided.

My father and mother were both craftspeople and worked. They raised us well. We were happy. We were learning.

Those first years, of course, I was young, so I don’t know much about the living difficulties. At home, they concealed those difficulties from the children. But I know that Armenia wasn’t prepared to receive hundreds of thousands of people. There were no apartment conveniences, no work, and even the food was lacking.

There were breadlines. I remember that I went every morning. But I never complained because everyone stood in line for bread. Food was lacking. It was the same for all. It wasn’t an object of complaint. Complaints in my family and circle basically stemmed from the lukewarm welcome given the repatriates.

They were probably officials, party members, they were probably forced from outside. I’m not sure. But it was due to that lukewarm attitude that a sort of trench was dug between repatriates and locals. A divide was created; he’s an akhpar, he’s a local.

On the other hand, the opportunity to receive an education was afforded us. There were three children in the family. All of us went to college and actively participated in the political and social life in Armenia. I took three separate student groups to Kazakhstan to work.

The repatriates brought various crafts with them. Standard of living traditions were brought to Armenia and the list of foods expanded. So too did clothing styles and perceptions of the world. To a small extent, Armenia broke out of its restricted situation. In the final analysis, the repatriation was mutually positive.

I had some wonderful friends in Armenia. I experienced the disadvantage of being a repatriate much later, after graduating university. I served as the secretary of Komsomol’s Communist Youth Union. This summoned me to work at the Komsomol Central Committee. After working there for one month they never appointed me to the post because I was a repatriate.

Sourik Haroutyunyan was the secretary. He told me, “Don’t worry, we’re looking for better work for you.” And they did. I was put in charge of a large enterprise. I was just thirty at the time. Later, I became a department chief at the ministry.

But there was something that tormented me. I applied to go abroad, to England, the first time in 1962. On the day I was scheduled to leave they denied my request, even though I had a passport and travelling money.

The Central Committee said that there was a misunderstanding and that I could go with the next group. I was denied yet again. Afterwards, they refused my requests to travel to Scandinavia and Lebanon.

They weren’t that politically mature during those years. We thought those decisions were coming from the Armenian government, but years later, we realized they were instructions being forced by Moscow. There was always the fear of traitors and spies being in the midst of the repatriates. An overall wave of distrust against the repatriates began.

For example, me and my friends discovered that there wasn’t one repatriate who had been accepted to work at the police division of the Ministry of the Interior. Nor was there any repatriates in the party apparatus at the Central Committee or the Regional Committee until the 1970s. Repatriates were represented at administrative posts afterwards.

I still don’t know if they banned me from going overseas as a tourist because I was repatriate or for another reason.

I should say that I tried, for the second time, to travel to Lebanon in 1975, if I’m not mistaken. I was refused again. I realized that there was some distrust regarding me. I decided to permanently leave and asked for a visa from my aunt living in Lebanon.

It took three years before they let me go. My case wasn’t in OVIR. They had stamped my file with a special mark and transferred it to the security committee. All the doors in Armenia were shut. I was forced to go to Moscow to resolve the issue. I had to pay huge amounts in bribes. We finally left for Lebanon. Due to the war, we moved to America.

I was well aware that I was going to a country where I didn’t know the language nor did I have a useful skill. It was highly unlikely that my linguistic skills or oriental studies would interest anyone there.

We are all here now. My sisters moved because I came here. After my sisters arrived, their husbands’ brothers and sisters also came. Just because I came, some fifteen families also moved.

The exodus from Armenia started like a chain reaction that continues until today. I didn’t move because I wanted better living conditions. I had a good job and a good apartment. I had a car, which was a big thing for me at the time. I had spiritual hardships, not economic ones.

My destiny is the same for all the others. Those who have left will never go back to Armenia. A miracle would have to take place, some mystical power would have to exist, to organize immigration to Armenia, but not like the one in 1947.