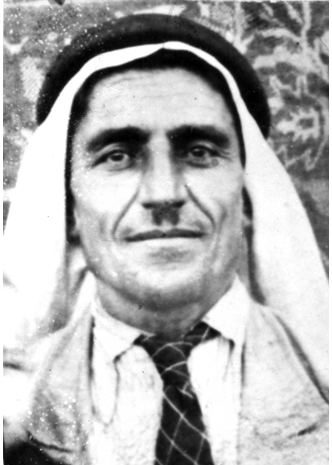

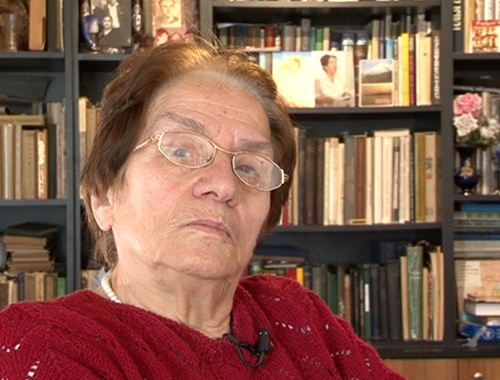

Repatriated from Syria, 1947 / Lives in Yerevan

Repatriated from Syria, 1947 / Lives in Yerevan

Lousik Ghourjian

We lived in a village. In 1946, when the repatriation started, a frenzy came over the village…we’re going to the homeland, we’re going. And we registered to go.

There was a man called Yeghishe Astvatzadourian, a prominent figure of Armenia. He entered the village at dusk and sees the flock coming from afar. Hundreds of sheep and horses. This man stands there, looks out, and is amazed. He thinks to himself ‘how can I keep these people from leaving.’ He calls my father and a few others to convince them. They dissent. ‘The road to the homeland has opened and we are going,’ they reply.

But they couldn’t sell their belongings. All around there were Kurds, people living in tents. Why would they have paid money if all the stuff would be left for them for free? Some people were able to take their goods to Hasichli ort Ghamishli and sell them.

We were the only ones who had a house in Ghamishli. It was a big house. My father loved to read and had many books. We children had a teacher, Miss Noyemi. Mrs. Nvart would help my mother. My mother came from the nomads and couldn’t read. They also taught my mother the language.

My brother arrived from Aleppo and we all set out for the homeland. They kept us for fifteen days in quarantine in Lebanon. We waited for the ship. My father’s female relative said, “Abraham, my boy, you’ve gotten rid of all your valuables and are going. But people from there have arrived and aren’t saying good things. Let me take you to see them.” There was a famous man, Charchoghlian, who had just returned. They took my father to see him. He said, “If you have ten years’ worth of food and clothes, then go.” My father said we have all that and that we like to work. We’ll work and live, said my father. We had a combine and a thresher. My father was hoping to go and bring them after we settled here.

They took my father to see another boy in Lebanon. That young guy had fled Armenia and showed my father the black bread and soap he had taken with him. He showed him the cotton vest he was wearing. My father thought he was one of those scoundrel dashnaks, a parasite, who didn’t want to work and thus escaped…

We boarded the ship, the Pobeda. It was the fourth convoy. The families from Syria and Lebanon joined those who boarded in Egypt. There were also people from Psherig, Kurdish speaking Armenians from the village of Sasna Psherig.

My father announced that we were passing through the Dardanelles and he took us all to the top deck. Standing on the balcony, all of us were overjoyed. “Ay caravan, jan caravan, follow your path. Armenians, from the desert, are going to Armenia.” (Translation of the Armenian song they sang)

In Batum, we saw that the ship Rossiya was berthed. On the water were oranges, bananas, sandwiches and candy…It turns out there was a quarantine. They were searching people to make sure they wouldn’t take any diseases to Armenia. They took all the food people had and tossed it. The Rossiya was emptied and then it was our turn.

The Kurdish speakers rebelled. They had gold and were well armed. The Syrian-Armenians got off, the Lebanese-Armenians got off. We remained. The people from the Ghamishli area remained because they had resisted. They said we wouldn’t get off the ship. They said they had sent a telegram to Mikoyan and that he replied not to search those people. And we weren’t searched. Those with gold and stuff were permitted to keep it.

They sent the more than one hundred families to different areas in Armenia. What were people from the fields going to in the mountains; in Artik, Sisian, Goris and Dilijan?

They sent us to Dilijan with Parounag, from our village. He had brought two stallions with him. He gifted them to Armenia. There was no work in Dilijan. They suggested to my uncle that he clean the stables. My father, along with neighboring repatriates, dug holes in January and February for spring tree planting.

My father went to the Central Committee twice, to see Grigor Haroutyunyan, asking that the people who had immigrated be sent to the Ararat Valley. “I gathered these people and brought them here, and you have scattered them to the mountains. There people are from the plains and can’t live in the mountains,” said my father. A few months later, they gathered the 15-20 repatriate families living in Dilijan and relocated them to the Mehmandar village, currently Hovtashen. But my father had since passed.

He had gone to Kazakhstan in the summer to reap the harvest with a scythe. We reaped wheat. My brother went and brought back sacks of wheat. After my father died, we lived on that wheat for several years.

My father only enjoyed the homeland for eight months. Upon returning from Kazakhstan, he went to the druggist and asked for a laxative. “Give me some English salt,” he said. They gave him one pill. One hour after taking it, his intestines turned black. After operating on him, they said he’d recover in three days. On the fourth or the fifth day, he died. We never found out why.

My mother moved to Yerevan with her six children. We rented a place in Arabkir. It was the basement, with a stable next to it. The hallway led to the stable, on one side, and to our room, on the other. Later, my mother bought a house. There was no one living in the area. There was a spring where we got our water. In the 1050s, when they piped ion water to the house, German prisoners of war did the work.

The repatriates brought great riches to Armenia. Some brought shoe factories, some brought printing presses. For example, the Bulgarian-Armenian Kaprielian brothers founded the Hairenik shoe atelier. They brought Dobel machines to Armenia. I worked there from 1953-1954. All of them were then deported and became common laborers.

People had come from France, Greece, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon and America…They all brought their culture and belongings. But they didn’t receive the repatriates correctly. There was lots of discrimination. They didn’t adapt. How to adapt when they said, ‘He’s an akhpar, but a good boy. She’s an akhpar’s girl, but a good girl’.

Our lifestyles didn’t mesh. It was only the national that could have united us, but the national had died to such an extent here that the locals could sing or anything.

Then they started the deportations. We had a neighbor, the tailor Seropian. One morning, in 1949, we found out that he had been banished.

At the wedding of our neighbor’s son, they wanted to sing about Antranig. The boy’s name was also Antranig, from Batum. They began to sing, “Like an eagle, you soar…” Before the song was over, they entered and summoned the boy outside. He went away for ten years.

My brother was attending college. He had some ‘literature’. One night, my mother put us to bed and burned that stuff. My father had song books. She burned those too.

Now, I don’t blame those who went back. Why shouldn’t they have returned? It was injustice, they saw no prospects. My four brothers left as well.