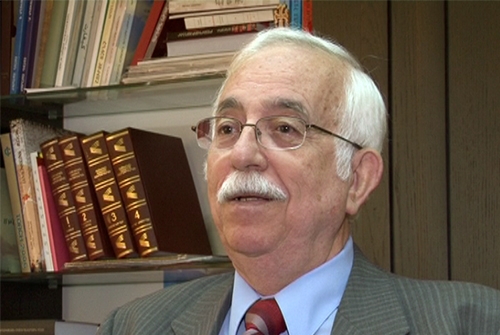

Literary critic, publisher (Beirut)

Literary critic, publisher (Beirut)

Jirayr Danielian

I was a child of six or seven. I remember it well. Our relative, Vahrij Jerejian, was in the repatriation committee. We lived on the first floor of a two story building and the Jerejian family lived on the second.

My father went to Aleppo at the time and brought back two huge and sturdy trunks. Later, I don’t know why, we didn’t repatriate. Vahrij Jerejian would always say, ‘Wait. The last ship will arrive and we’ll all go together.’ This despite the fact that his younger brother Zohrab and three or four students went. One was Kevork Khrlobian.

Those trunks remained in our house, Later, we moved from the Armenian neighborhood to the town center and those trunks were the idle place for playing hide and seek. We’d fit inside to hide. Later, we stopped using those trunks .

I also remember that the families of my two aunts were among the crowd of repatriates. My parents and I went to the port called the Karantina that still exists today. There were crowds of joyous people there singing songs like ‘hey jan caravan’, hey jan Yerevan’. When the ships left, we ran to the house of a friend with a good view of the sea. From there, looking out at the ships on the horizon, we wished them a final farewell.

The communist party issued an order that if you were a Tashnag, you would have to resign from the party publicly, that’s to say in the press, at the time of repatriating. There were such unfortunate occurrences, that put a damper on the happy atmosphere.

I also remember that some of our relatives who repatriated wrote letters saying that the people had been deceived. Now, is ‘deceived’ the right word or not, I don’t know. I just know one thing – that at the time, Armenia was described as paradise.

Now, if we approach the issue from a moral perspective, whatever conditions Armenia is in, the country is a paradise; no? That’s to say, it’s the motherland. However, I think that the leaders of the time should have been more realistic with the people, telling them they weren’t going to a paradise and that they would encounter various difficulties. This is especially true when the Soviet Union had just exited WWII and our small country had given 300,000 lives. The country had become poorer and was orphaned. The industrious forearm of the Armenian had reached its minimum. All this should have been explained so that people could have based their decision to go or not accordingly.

On the other hand, there were also conversations making the rounds that if the population of Armenia dropped to below one million, it might cease being a republic and became an autonomous region. Now, I don’t know if this was correct. But, we must accept that at a certain period the population of Armenia increased.

Later, I also assume that the economic concerns were factors that had more of an impact in recruiting working hands. Don’t forget that most of the repatriates from Persia and Syria were villagers. They already lived in rural conditions and perhaps it would be easier for them to continue their lives there in similar conditions.

The repatriates from France, America and Lebanon, those with a good standard of life, perhaps suffered the most. I remember one incident. The French foreign minister, I don’t remember which one, visited Armenia. French-Armenians, those who had repatriated, staged a protest in his presence. And, I believe, that many French-Armenians returned much earlier fie to the intervention of the French government. One of those was, if my memory doesn’t betray me, was Meline Manouchian, the widow of Missak Manouchian.

The main exodus from Armenia took place in the 1970s and 1980s. My relatives left Armenia in the 1980s.

I have decided not to leave Lebanon. I made the decision in 1975. If I were to leave Lebanon, yes, the address, my only address would be Armenia. Perhaps it’s due to my interests that I say so. I am involved in philology and in literature. I’ll go and pursue these things in the homeland. The most suitable place to do such work, I believe, is the homeland.