Poet, Literary Critic (Beirut)

Poet, Literary Critic (Beirut)

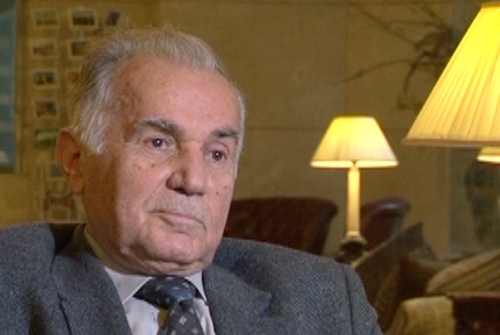

Aram Sepetjian

We were children of a family forcibly evicted from our Cilician birthplace. We settled in Lebanon in 1938. At the start of the immigration to Armenia, my parents applied and received the first card to go.

We prepared our big wooden trunks, but as things worked out, they left us here during those two months and took people they regarded as more correct. So, we got used to the idea of remaining here. But I had friends as distant relatives who were a part of that immigration, or as I say, national assemblage. They participated and went to the homeland.

However, before they went, they should have been told that they weren’t going to paradise; that the Soviet Union wasn’t paradise. They should have been objective. And them, our friends who believed in Armenia, would tell us, stay, don’t come.

As to why the local people didn’t want the repatriates, well, they had experienced such bad times during the war years, that it seemed that those repatriates had come and settled in Armenia just to make their bad situation worse. And what happened? For example, if they had been getting one loaf of bread, now, that loaf was split in half.

Of course, a number of things happened that later, when we heard about them, we didn’t like. We didn’t like the “akhpar” stories and jokes. We felt insulted. Why they called us such things, we don’t know.

Buoyed by the 1945 victory, they went and settled in Armenia, and some of them were forcibly deported or relocated. It was impossible for that to be accepted. For the Armenian people, there was no immigration. They took people elsewhere to build. But I ask you, how many thousands were subject to that forcible exile – be they intellectuals, individuals, craftsmen, workers? We don’t know.