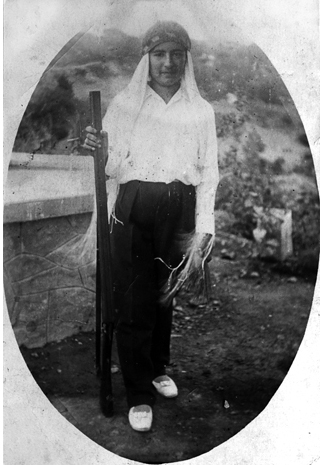

Repatriated from Aleppo, 1946 / Lives in Yerevan

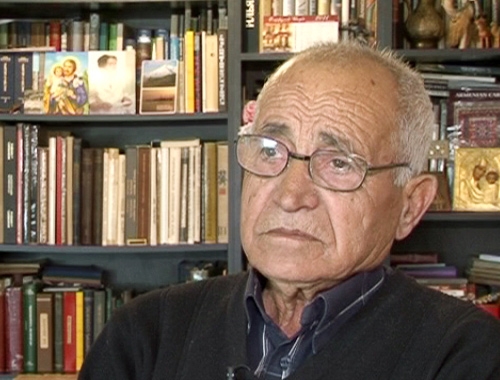

Repatriated from Aleppo, 1946 / Lives in Yerevan

Garbis Tashchian

We arrived in Armenia is 1946. My parents so loved Armenia that they didn’t even sell the house before coming. Friends of my father came around and said, “Mihran, where are you going? You’re leaving such a fine house and all.” There were people who had escaped from Armenia who brought bread with them. They showed the bread to my father. It was all dough. My father said, “No, you are against [going] and are telling lies.”

In Yerevan, they moved us near the Tokhmal gyol. It was called eastern Sari neighborhood. There were seven of us. Some people came to our house and brought breads and salami. It was dried kalbas. My mother didn’t know what to do with it…We put it in a dish and brought it to the market, the present-day Tashir market, and sold it. Then, a policeman came and took us to the police station at the market.

My mother said, “My boy, things don’t look good. Let’s flee.” I told her we couldn’t. There was a policeman outside. So, we threw the salami away and escaped, when my mother went to the toilet.

Later, I was accepted at a trades school. I was 14. It was good there for about two years. There was eating and drinking. The cafeteria gave you nine hundred grams of bread every day. But I didn’t become a lathe turner. My eyes weren’t good. I went to work with my father, who worked as a laborer in Aleppo from the age of eight. We built bridges over the Gedar River here with the German prisoners of war. Then, we built private houses here as well. When I turned forty, I started to make the Armenian stone crosses.

There was a master jeweler who had come from Iran. I learnt how to make the khachkars from him. One day, he had gone to the Monument. There was construction going on there and he asked the engineer for a job. When the engineer found out he was a jeweler, he exclaimed, “We build walls here. It’s no place for a jeweler.” Rafayel Israyelyan placed a stone on the ground, pulled out a pencil and drew a decoration on the stone. The Iranian guy finds a nail and starts to engrave the stone. Israyelyan says, “Stop, you’re my craftsman.” The guy, Hrachik Stepanyan, was his name, worked on the Monument. He carved the four bas-reliefs there. Later on, he worked in Lenin Square and elsewhere. He was the shah’s jeweler in Iran. Letters sent to him would be addressed – Lenin Square, Stepanyan, Hrach – and he’d get them.

Yes, I knew that they were exiling some of the newcomers, but I didn’t inquire about it. We’d get up in the morning and see that a wooden cross had be nailed on the neighbor’s door. They came in the night and took them away. And just for going to the Dashnak club to play backgammon. They took people away who couldn’t hold anything but a needle in their hand here. There, they’d split logs.

People were needed in Siberia. They told Catholicos Chorekchian “We’ll give you twice as much land as the Turks seized from you. Go and live there.” The Catholicos replied, “But how will I take Ararat and Etchmiadzin there?”

To be honest, nothing happened to us. We were neutral. Back then, you didn’t know who the person next to you was. That’s why we didn’t get mixed up in anything. Then again, my uncle had some trouble.

The boys were helping the old folk with their luggage on the ship that was to take us to Armenia. In Beirut, my uncle’s son had taken somebody’s luggage and brought it to the ship. But my cousin didn’t leave the ship. He hid away in one of the lifeboats. That’s how he reached Armenia.

They took him to the orphanage. He was thirteen or fourteen. His father said the boy had fled to Armenia. My uncle was forced to come to Armenia. One day, he told his son, “Let’s go back.” But he didn’t tell him they’d be escaping. They’d sleep during the day and travel by night, through the hills and valleys. They’d bribe villagers who saw them not to report them. But someone went and reported their whereabouts to the border guards. Before being captured, they were able to bury their watches in the ground and put a stone on top. This way, they could come back later for the watches.

They went to jail. We used to bring them food. They were released after a year or so. He married a woman from the village. He died later on. I carved his tombstone. I started making stone crosses from then on with Hrach. Later on, they let Hrach and his family go to America. His daughter-in-law was in a dance group. They went to America and back twice. They saw it was a good country and they all relocated there.

My sister is in America now. But I don’t like to go. I went twice but didn’t like it there. I went for a vacation, not to stay.