Repatriated from Egypt in 1948 / Currently resides in Glendale (California, USA

Repatriated from Egypt in 1948 / Currently resides in Glendale (California, USA

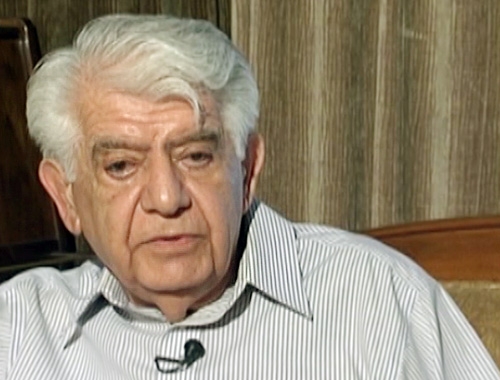

Vahe Gabouchyan

Our family repatriated in 1948, but the movement took off in the Diaspora in 1946. In Cairo, where I was born, people rushed to be the first to leave for the homeland.

Truthfully, the enthusiasm was boundless. Much work was done to show Armenia in a positive light. Even songs were spun, one of which I still remember – “A wonderful telephone in my apartment. You can speak to four at once. Hello Albert, dear Aram...”

Our family had a good life and the reason for repatriating was, of course, patriotism. The gaze of my parents was directed towards Armenia. After the Nubarian National School, I graduated from Lincoln College at the American University. We then came to Armenia.

We experienced the first sign that our expectations weren’t to be met in Batum. Firstly, they meticulously checked the books and food we had brought. Then, they gave us some bread that confused us; was it cake or bread?

We spotted Yerevan from the truck. It was a gray city with no traffic. You really got a sense of how terrible the war was that the country had gone through.

They gave us an apartment in an unlivable corner in Yerevan’s Arabkir neighborhood. A year before, a repatriate family from Greece had taken a loan out from the government. Most had been spent on living expenses, as many had done. The building remained half built. It had no doors or windows. My mother kept telling us – Don’t despair. Pay attention to your studies.

I was accepted at the economics faculty of Yerevan State University, and my brother at the philology faculty. I attended the first shift of classes and my brother, the second. This allowed the both of us to get employed at a furniture factory as one person, replacing one for the other. We were laborers unloading the trains. The factory had just been built.

Nevertheless, I still graduated the university with honors and was accepted as a post-graduate student. I defended my dissertation and received credentials.

My older brother was given the title of meritorious professor at the Lomonosov University in Moscow.

Of course there were problems between the locals and newcomers. A majority of the population in Armenia didn’t receive us kindly. They called us names and such. I explain such behavior due to the fact that, first of all, a people living in difficult conditions and having just experienced a war saw a large mass of confused people arrive and ask for privileges. In the eyes of the locals these were privileges, but for the newcomers these were normal living conditions.

The government, in turn, acted incorrectly. For example, I didn’t serve in the army because they told me I didn’t have any military training. I didn’t have any because I was a repatriate.

But, I didn’t feel the moment when I became an Armenian local. It happened unconsciously because, truly, there was devotion.

My compatriots would go to parties in the evening. They would organize dances in their homes. That wasn’t for me. I started to live more like the locals and adopted the local customs.

The young repatriates had an easier time integrating than the older folk. For example, until the end my father never understood. He’d tell me, “Where have we come? This isn’t a soviet country but a mysterious/enigmatic country.”

Had not even one repatriate arrived in Armenia, our country, Yerevan, would have turned out the same. But, truly, the repatriates brought a new culture, each from their own country.

Diaspora Armenians played a big role, even regarding lifestyle things. They had no idea about drinking coffee here, nor did they eat olives. I won’t even talk about quality culture or the prominent artists that immigrated.

Later on, I emigrated from Armenia because I was very insulted. In 1989, the enlightenment and higher professional education ministries were to be united. It was a good decision. But I found out from the newspaper that I wasn’t listed in the new governing body. I was very insulted and left the homeland. (Mr. Gabouchyan was working as a deputy education minister in charge of colleges and universities.)